It was raining outside my tea room. Polly my dog was happy in her house. I was in heaven painstakingly (not contradictory in terms) typing the French letters (the annoying à and é and ç) into my on-line translator. The music was vibrating the thin rice-paper calligraphies on my mahogany-colored wall.

I consulted a couple of translations for Lionel Poilâne's Pain Rustique recipe in his Le Pain par Poilâne, page 143. The 390-page book contains a dozen recipes. I studied the translations. I read the recipe very carefully. And in the end, I said to myself, disbelieving, "Is that it, so simple?" "Is this the recipe that makes the famous Miche Poilâne?" (No.)

One of my sisters told me there is a single product hawker's stand in Taipei which sells red bean pancakes. Any time of the day you go there, there is a long queue waiting to buy the man's red bean pancakes. He has a dedicated pot to cook his red bean paste at home; the pot is never used for anything else. He has several other dedicated utensils for the job. My sister gave me his recipe. It sounded so simple, I said, "Is that all? You are not leaving any steps out?" She said, "No." She gave me the man's list of ingredients: red beans, sugar, flour, and water. I said, "You are not leaving any secret ingredients out?" She said, "No."

Still disbelieving from reading the Poilâne formula, I got up from my chair and walked past a neglected pile of books left there since I came back from Taipei last October. At the rate I buy books there is no way I can finish reading all my books in my lifetime, but I keep on buying. The postman, the DHL man, and the Fedex man, as well as the occasional sub-contractor for Australia Post, all know there is somebody whose name sounds like (to pronounce slowly) "shopping" that lives behind that gate (and what an annoyance having to ring the bell for the gate to open!).

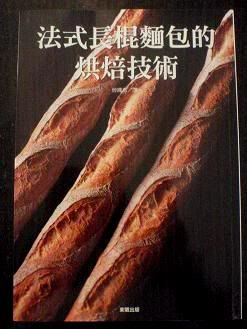

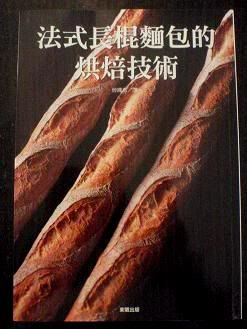

Anyway, I retrieved from that pile a book which is, on the surface, dedicated to baguettes, a Mandarin translation of the best Japanese baguette formulas. And, boy, can you get any more perfectly shaped baguettes than those any where else in the world? My oh my, the formulas are so detailed! And, interesting!

Baguette no Gijutsu (Baguette Techniques), published by Asahiya Shuppan, Japan

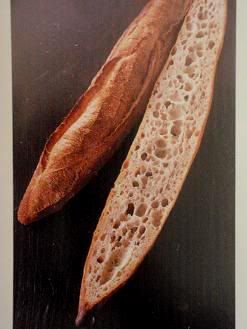

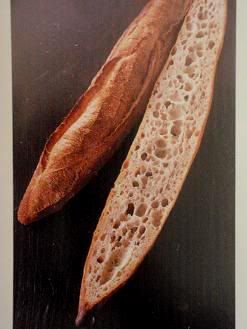

right: Totszen Baker's Kitchen, Yokohama (page 28)

middle: Fournier Bakery, Osaka (page 8)

left: Lobros Bakery, Tokyo (page 124)

The way I see it, this book is about methods of pure fermentation of flour. Baguette is only the form in which the result is show-cased; the bread could be in any shape or form. There are 35 very detailed baguette formulas by today's top Japanese bakers in a very easy to follow format. The bakers play with fermentation possibilities in a wide ranging ways and dough hydrations of between 57 and 83%. The book reads to me like 35 flour fermentation love stories. The baguettes are solid works of fine craft and done in tightly controlled environment (the Japanese way!). Using the simplest ingredients, their objectives are all the same: to bring out the best flavour in flour through their individual fermentation methods. Only a third of recipes use levains, and not even at high baker's percentages, for a more clean taste of flour. Some use other pre-ferments; but pre-ferments are nothing new. What I find interesting is pre-fermenting the main dough flour.

Have you ever heard of autolysing flour and water for 12 hours? Maybe you have, but I haven't. With this post, I am making baguettes using Fournier Bakery's formula on which the gorgeous looking crumb pictured in the middle above is based. The book says Fournier won the 2006 French Baguette Competition organized by Torigoe, the oldest Japanese miller of French style of flours.

Fournier Bakery's baguette formula

Ingredients in baker's percentages

- 100% bread flour (I used 650 grams of Australia's Kialla Organic unbleached plain flour)

- 70% water (I had 455 grams)

- 15% liquid starter (I had 98 grams. See note * below)

- 0.1% instant dry yeast (I used two-thirds of a 1/3 tsp)

- 1.9% salt (I had 12 grams)

Overall dough hydration is 72.1%. My dough weighed about 1200 grams. I did three times the formula in three days, totaling 18 baby baguettes of 200 grams each (see below).

Note *: As most of us are weekend bakers, it is best that our starter undergo at least two refreshes (ie, refreshment build and levain build) before being incorporated into the final dough. I did three builds for my levain, each time discarding all but 20 grams for the next build. I timed the last build to coincide with the 12 hour autolyse of flour and water (see step 2 below).

- Place only flour and water in the mixer, turn on first speed for two minutes.

- Autolyse for 12 hours at 16 ºC. (I did about 9 hours. As it is summer here in Australia, my temperature averages around 25 - 27 ºC.)

- Add liquid starter and instant dry yeast and mix in first speed for one minute. (The book says the levain is ready for use when its pH is 3.7. I had no way of knowing the exact pH of my levain but because it had just gone through 3 builds, I would guess that the pH value might be a lot higher than 3.7.)

- Add salt and mix in first speed for 2 more minutes, and second speed for 1 minute and 30 seconds. When kneading is complete, the dough temperature should be 22 ºC. (Note: I did all my mixing and kneading by hand. It was very messy, especially trying to get the liquid starter mixed into the dough. I did not use ice water to try to get my dough temperature exactly as per the formula. I figured that I would just watch the fermentation carefully.)

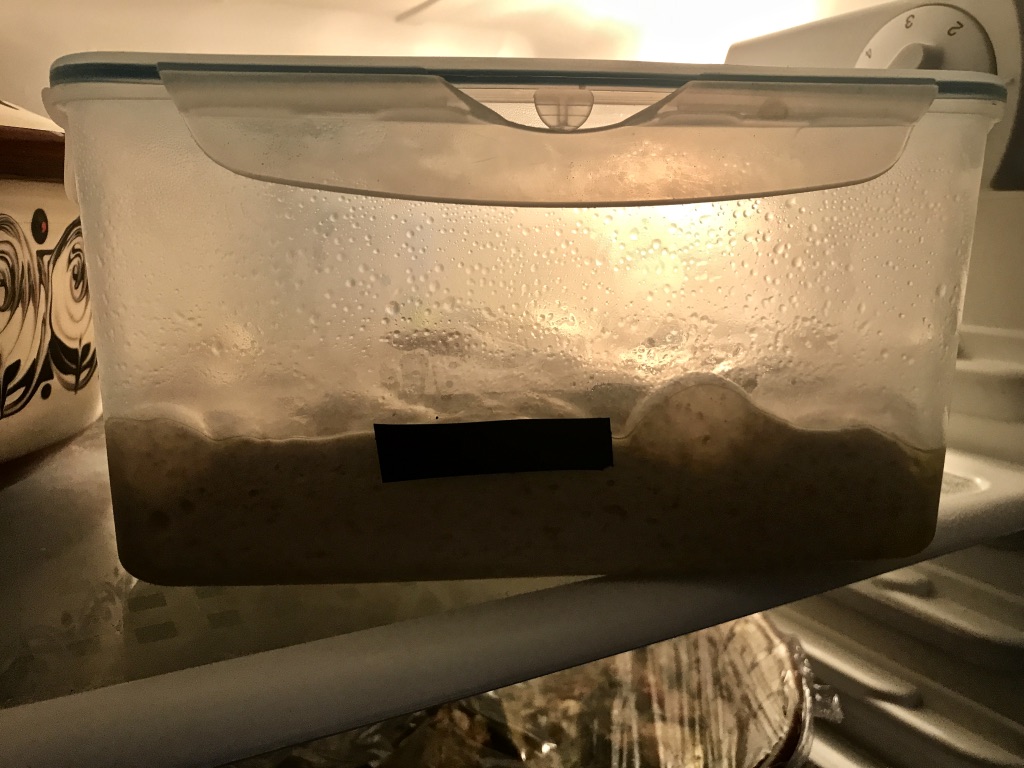

- Bulk fermentation is 3 hours in total at 22 ºC as follows: three times 2 letter-folds in a plastic container at 20 minutes intervals, then twice more 2 letter-folds at 60 minutes interval, totaling 5 times. (As my room temperature and dough temperature was about 25 - 27 ºC, I did only 2 hours bulk.)

- Divide the dough into 350 grams pieces and pre-shape them (I divided my dough into 6 pieces of 200 grams each because my baking stone is small, 34 cm x 34 cm.)

- Shape into baguette, 60 cm long. (I shaped mine into 32 - 34 cm long).

- (Note that it should only be 30 minutes from Divide to Shape, including the rest in between, during which time the dough pieces should be placed in temperature controlled room at 22 ºC.)

- Proofing is 60 minutes at 22 ºC and 70 degree humidity. (The book says when the dough completes its fermentation, its pH should be 5.2.) (For the last 30 minutes of proofing, I moved my dough into the refrigerator as I was afraid that it might over-prove.)

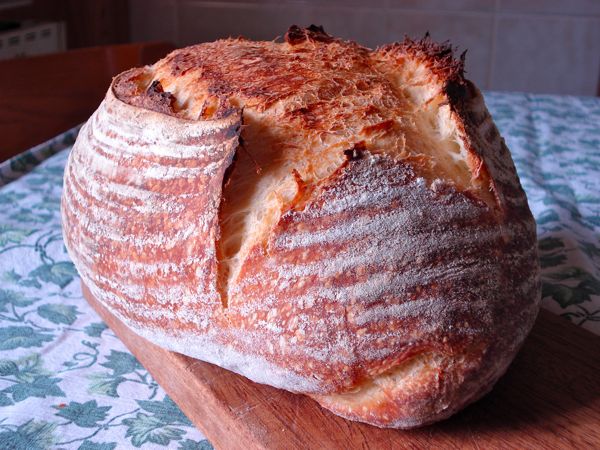

- Pre-heat oven to 250 ºC. Score the dough with 7 slashes. Steam the oven before loading the dough. Once the dough is in the oven, turn the oven down to 240 ºC. After 3 minutes of baking, steam the oven again. Bake for a total of 30 - 32 minutes. (My dough only needed 23 minutes of baking at the highest temperature my oven could go. I could only manage 4 slashes on my dough.)

To recap: Fournier's fermentation is 4 1/2 hours all-up at 22 ºC. I did 3 1/2 hours at 25 - 27 ºC, including 30 minutes in the refrigerator, which had an added advantage of chilling the surface of the dough for easier slashing.

The challenge of baguettes to me is how to shape them uniformly. There is no better way than repetitive practice. It was only towards my last 3 baguettes (those pictured above) that I worked out how to do them with same length and thickness. The key for me is, after pre-shaping and rest, pat the dough out to very flat (not to worry, I was not squeezing the gas out by patting). Then, use minimal movements possible to shape the dough. I find that excessive handling serves no purpose. Out of the 18 baguettes that I made, the three next best ones are below:

I find slightly under-proof works better than slightly over-proof. As my dough pieces were small, just 15 minutes more than necessary could make it over-proved. Once the dough is done fermenting and ready to go, no amount of chilling in the refrigerator can arrest it because of the internal dough temperature. The flavour will still be good but oven spring would suffer.

It would be interesting to try out more formulas in the book to learn more ways of pure fermentation. There is nothing wrong of using other type of flours (for instance, various whole grains flours) on these baguette formulas, paying attention to temperature and time issues etc., and see how they affect fermentation outcomes. I learn in this book that there are infinite possibilities.

Just as I was cleaning up from today's mess, it's almost time to go and pick up my son from his tennis. I tied up two baby baguettes to give to Andrew's coach. Don't people just envy us because we possess these presents to give away?

I was late collecting my son. When he saw me, he said, "Soft effort, Mum, soft effort." Gee.

It has stopped raining now. It is lush and green outside the window. Polly would not be allowed to go out for a while yet, not until the grass is dry.

Shiao-Ping