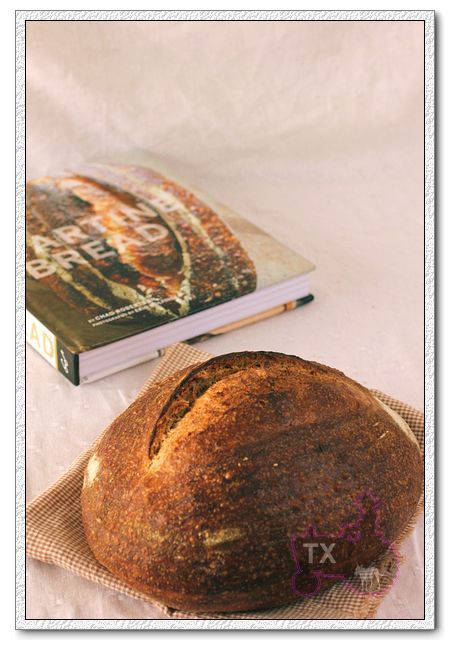

Tang Zhong, Ricotta, Scalded Multigrain with and without, Cranberries & Pecans

We use a lot of cranberries around here mainly as part of our snockered fruit bled we put in so many baked good. Evon published her beautiful cranberry bread she made her Mom and we have been making a bunch of different breads with dried fruits and nuts of late. The only ones we missed were cranberries and pecans. Then we saw a beautiful cranberry and pecan batard at Whole Foods when we were there stocking upon whole grain berries.

That sort of moved the cranberry and pecan bread up to the top of the list. My apprentice just couldn’t leave it at that so she went - with whole; rye, spelt and wheat in the levains only along with some corn flour in dough. We are trying to get out tongue around corn flavor wise and have seen it so many bakes of late like Janet’s Anadama Bread.

Lucy found some apricot soaking water from the last bake (which we added the cranberry soaker water to) and ricotta cheese in the fridge. She also scalded up multigrain berries as she does for just about every bread. It must be a German thing. She also used our normal flavor, color and rise enhancers of malts, Toadies and VWG. Not including the multigrain scald, we kept to our healthy and tasty minimum of 30% whole grains.

Because of the Tang Zhong, ricotta, scald and re-hydrated cranberries, this dough does not look or act like a 70% hydration bread. It is very wet feeling, like 78% or more - so not quite ciabatta. The Tang Zhong took 25 g or the flout mix and 125 g of water not included in the formula to make the roux.

We built 2 separate levains over 3 stages. One a YW and the other a rye sour. Both levains had doubled at the end of 2nd 4 hour stage. At the beginning of the 3rd stage, right after feeding, we refrigerated the levains for 12 hours. The next morning we took them out of the fridge and allowed them come to room temperature and double again in 4 hours.

We did our usual 4 hour autolyse, starting when the levains came out of the fridge, including everything except; salt, ricotta, YW and rye sour levains, the scald, cranberries and pecans. When the autolyse met the 2 levains, we added the salt and did 10 minutes of slap and folds. After a 15 minute rest we did (4) sets of S&F’s on 15 minute intervals. On the first S&F we incorporated the ricotta. On the 2nd we put in the scald.

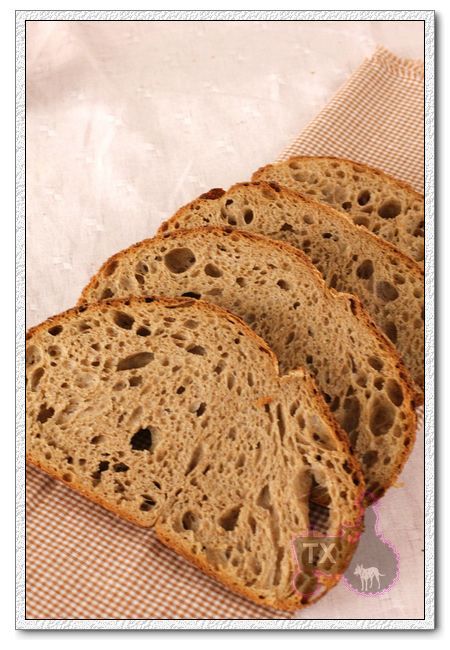

After the 2nd we divided the dough in half. On the 3rd we added the cranberries and on the 4th we made sure everything was incorporated for one half. The other half of the dough was S&F’ed without the fruit and nuts. This way we get a breakfast toast and a lunch sandwich bread.

After an hour of counter fermentation the dough was retarded in the fridge for 15 hours. In the morning they were retrieved from the fridge and allowed to come to room temperature for 1 hour before being shaped into a batard for the fruit and nut version and an oval for the plain.

Both were placed into a trash can liner to proof for 2 hours before Big Old Betsy was fired up to 500 F with Sylvia’s steaming pan and David’s CI Lava Rock steam in place. Once Betsy beeped she was at temperature we waited 20 minutes before un-molding the bread, scoring and placing onto the bottom stone.

After 5 minutes we turned the oven down to 475 F. Our oven reads 25 F low so adjust your temperature accordingly. After a total of 15 minutes of steam we removed it and turned the oven down to 425 F, convection this time. We rotated the bread every 10 minutes and after 20 minutes without steam the bread reached 205 F in the center.

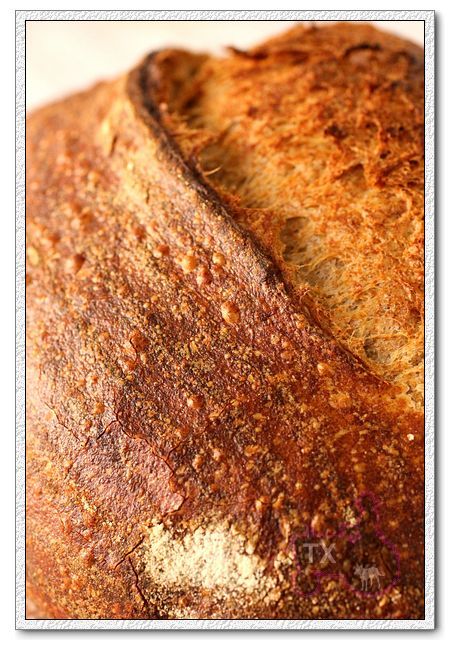

We turned off the oven and left the bread on the stone, with the door ajar for 10 minutes to crisp the skin before removing it to a cooling rack. The crust browned nicely with small blisters and went from crisp to softer as it cooled. The spring and bloom were OK too. The cranberry, pecan version browned more for some reason.

The crumb of both versions was about the softest, moistest and tastiest we have ever managed to bake into any bread. it is just fantastic as a sandwich bread and we hope it toasts just as well for breakfast in the morning. It is like eating two different breads one more cranberry sweet and pecan nutty. Both are terrific! Thanks Evon for the cranberry inspiration, to Ian for the cheese and to my apprentice for the nuts.

We love spaghetti and meatballs. Hopefully the plain version will grill up nicely for garlic toast or bruschetta or breakfast.

Formula

YW and Rye Sour Levain | Build 1 | Build 2 | Build 3 | Total | % |

Yeast Water | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 7.21% |

Rye Sour Starter | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 2.37% |

Spelt | 13 | 13 | 13 | 39 | 4.62% |

Dark Rye | 34 | 34 | 39 | 107 | 12.66% |

Whole Wheat | 13 | 13 | 13 | 39 | 4.62% |

Water | 20 | 60 | 25 | 105 | 12.43% |

Total | 140 | 120 | 90 | 350 | 41.42% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Levain Totals |

| % |

|

|

|

Flour | 195 | 23.08% |

|

|

|

Water | 155 | 18.34% |

|

|

|

Hydration | 79.49% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Levain % of Total | 19.14% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dough Flour |

| % |

|

|

|

Corn Flour | 50 | 5.92% |

|

|

|

AP | 600 | 71.01% |

|

|

|

Dough Flour | 650 | 76.92% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Salt | 12 | 1.42% |

|

|

|

Apricot/Cranberry Water 100, Water 300 | 400 | 47.34% |

|

|

|

Dough Hydration | 61.54% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Flour | 845 |

|

|

|

|

Apricot & Cranberry Water 100 & Water | 555 |

|

|

|

|

T. Dough Hydration | 65.68% |

|

|

|

|

Whole Grain % | 30.89% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hydration w/ Adds | 70.15% |

|

|

|

|

Total Weight | 1,829 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Add - Ins |

| % |

|

|

|

White Rye Malt | 3 | 0.36% |

|

|

|

Red Rye Malt | 3 | 0.36% |

|

|

|

Toadies | 10 | 1.18% |

|

|

|

VW Gluten | 15 | 1.78% |

|

|

|

Cranberries | 75 | 8.88% |

|

|

|

Pecans | 75 | 8.88% |

|

|

|

Total | 317 | 37.51% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weight of cranberries and scald berries are pre re-hydrated weights |

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scald |

| % |

|

|

|

WW Berries | 33 | 3.91% |

|

|

|

Rye Berries | 33 | 3.91% |

|

|

|

Spelt Berries | 34 | 4.02% |

|

|

|

Total Scald | 100 | 11.83% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tang Zhong 25 g of flour was included above but the 125 of extra water was not | |||||

Die besten Rezepte aus der Allgemeinen Bäckerzeitung - Brot, Brötchen & Snacks

Die besten Rezepte aus der Allgemeinen Bäckerzeitung - Brot, Brötchen & Snacks