Need help pin pointing where things go wrong with my seed & oatmeal bread recipe

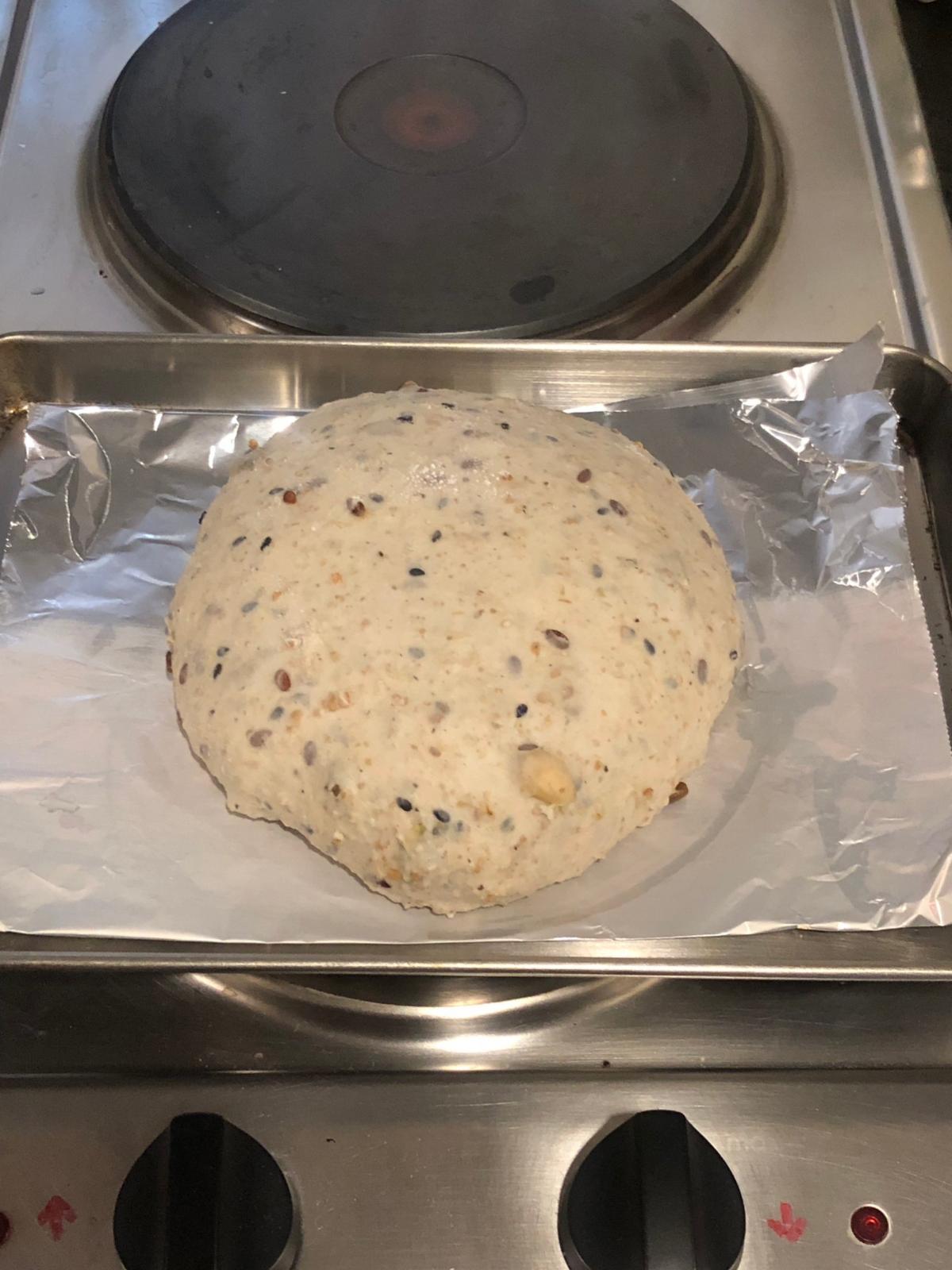

So, today I tried to adapt my sandwich bread recipe I'm fairly confident in into a multi-seeds & oatmeal bread and almost ended in a failure. I might have recued it, maybe? The bread is cooling on the rack now and result can only be ascertain after I slice in. Now, this one is only the experimental one, which, thank god I second guess myself and doing this one first, and I only have one more shot that I don't want to mess up (at least not this bad), so I'd like some more eyes to help me scrutinize where I went wrong. I'll post my speculations and detail recipe later, but first, let me explain my thought process how I get here.

It starts off when my wife mentioned she love this one multi-seeds bread from a supermarket chain near my place, which I find it a bit relatively expensive and, as a proud hobbyist, think I can one up them. Normally my wife wouldn't be happy with me baking bread that much with various personal reasons in our family, and one also being that bread isn't our staple here in SEA. Now, though, since she greenlit me to bake this weekend, I hope to take this chance to turn things around to bake this multi-seeds bread she seems to like.

So, I started off with a recipe for milk sandwich bread that I'm fairly confident in, and, from digging around in this forum and the internet, I arrive at the conclusion that:

1. I'll use a mix of pumpkin, sunflower, flax, and sesame seeds of 2:2:1:1 ration, coming to a 20% in baker's math.

2. I'll toast them and soak them until fully hydrated, and I can drain and add them right into my recipe and it shouldn't mess up my hydration, or at least, not too much.

3. Since my wife is more and more health conscious these day and I heard that oatmeal can improve the fiber content in bread greatly (the kind that is normally lack in bread or something of that sort), so why not? searching around the internet give me a recipe that use about 20% seeds and 25% oat in the recipe just fine. Although their total hydration including all the oats and seeds are at 65%, while mine is about 75%+/-3 without the seeds and oats, I decide to go with 20% oatmeal toasted and soaked before wringing out the excessive water and add into the recipe. With the same train of thought as the seeds, that shouldn't mess up my hydration, or at least, not too much... right?

4. Again, since she seems more into whole grain bread, I decide to bump up the whole wheat-rye starter proportion from 10% of the flour to 20% (just the flour part, so, as it's 100% hydration, its total weight went from 20% to 40% of flour)

So, with all the tweaking, this is the intended test run recipe:

Total flour 102g, hydration ~78.5%

- 46g Tang Zhong (20g AP flour+ 2g rice flour + 24g boiling water)

- 40g Poolish (equal whole wheat+rye, in place of 100% starter)

- 60g AP flour

- 40g Milk

- 6g Sugar

- 6g Butter, melted

- 2g Salt

- 1g Yeast

- 20g Oatmeal + 20g Mix seeds, all toasted, soaked, drained, and wrought*

Except the last item, the rest is my adjusted standard sandwich loaf that work well in the past; normally there will be only 20g starter/poolish and the flour and water will go to AP and Tang Zhong, respectively, instead (so, 70g AP and 34g boiling water)

My intended process was:

- Prepared my Tang Zhong, mixed poolish, and toasted and soaked to seeds and oat.

- Combine everything except flour and mix well, then add flour and let it autolyse for 30 minute.

- Slap and fold until gluten develop well, bulk ferment, shape, proof, bake

In retrospect, the first bad sign I should have noticed was that my Tang Zhong might have some gluten development, so it might have not gelatinized properly as I might have let my water temperature dropped too much. Another thing was that, I measured the weight just in case, and all the soakers combined came at about 100g, from a dry weight of 40g, so that's 60g water inside it (150% absorption); but I just brushed it aside.

Anyway, first thing that went off was I ended up with 1-1.5 hour. The poolish might not have ripened, but I intended to just let it ferment as much as possible before I mix the dough and add the rest of the yeast later. Then, the first real bad sign I notice was even after that long autolyse, I could barely find any strength developed in the dough. After a few minutes of slap and fold, which was more like scooping up & dropping the batter, I can only see some string appearing and thought, developing gluten from this would be next to impossible and decide to add 15g more of AP flour first to see how it went. After mixing it in well, the dough is still very slack, but I could see some more gluten development right away, so I decided to give it a shot just like that and managed to slap and fold it into shape in the end. That what I did to rescue the dough, maybe? Not sure if it's too wet and gummy inside or not.

After the fact, I come back to recheck the baker's math.

If I treat all the dry weight of a soaker as part of the total flour (so, extra 40g), and the water they absorbed as part of the water (extra 60g), my dough will be at 98.5% at the beginning, and after adding 15g of flour, that came down to 89%. This is relatively align with the feeling of the dough that I got at each stage.

Here's my questions:

1. Is my conclusion that, I should take the soaker into account as dry ingredient, and add 1.5x of their weight in the fluid part of hydration equation sounded?

2. If I just cut down the hydration of my original recipe to incorporate these extra water and dry ingredients, do you think it will have enough gluten strength to hold everything? My reasoning is that, I'd treat the 20% flour in Tang Zhong and another 20% in preferment as effectively not producing gluten since they are gelatinized and fermented, respectively. That leaves only 60% of the flour that producing gluten, 40% not producing gluten, and extra 40% are seeds and oats.

3. With that train of thought, should I actually treat this as a loaf with 142g of flour instead (22g in TZ, 20 in preferment, 60 in Main Dough, and 40 in Oat&seeds,) and increase sugar and butter proportion accordingly?

4. Any suggestion to prevent me from messing up the whole 300g flour loaf that I'll bake, maybe, tomorrow or the day after? My concern right now is that, I'm not sure if the 40% added seeds make my loaf bigger or not, or the added bulk is off set by the less rise the dough get from the seeds and oats. It feel like it is bigger to me right now. My issue is that I use a small toaster oven and 300g straight dough is as full as it can get that I got a spot burnt crust sometime due to the loaf rose up too close to the heating element.

It's been a puzzle to me how to take the water in a tangzhong or scald into account. I've concluded that at the least I should consider all that water to be part of the total water.

I consider that flour in a preferment to be part of the gluten-forming flour (if it's wheat, anyway). If you haven't fermented it into soup, it will still form gluten. You can verify this by stirring up or kneading the preferment. The gluten effect will show up right away.

When you change a recipe by adding a new flour or other ingredients that might or might not soak up more liquid, it's a good idea to hold back some of the planned water. You can always add more later. How much to withhold? I don't know a general rule, but I tend to hold back something in the vicinity of an ounce/30g.

If you end up with a very wet or slack dough, it can be useful to shower it with a lot of flour during shaping. Don't make a preform, go right to shaping the loaf.

Hope this will be helpful.

TomP

Thanks for the response, TomP. You're right about the preferment. It's just that my preferment was half rye half whole wheat so I tend to think maybe I should just forget about it as it should not make much difference, or not?

As for the tang zhong, from what I have been told, water in tang zhong will be counted toward the total hydration as usual, but the feel of the dough will be closely toward the dough with that total hydration minus the percentage of flour used in tang zhong (provided that at least the same amount of water have been used). So, for a base recipe with 80% hydration, if 20% of flour is used to make tang zhong, the overall hydration is still 80%, but the dough will behave like a 60% hydration dough. I normally use 20% flour + 40% water, but the excess water wasn't added to the deduction, it just made the mixing process of the tang zhong easier and more foolproof (gelatinized starch soak in the water really well and get stiff & sticky, incorporating all of the flour become harder for 1:1 ratio, and more water mean the temperature drop slower, so they gel properly before it gets too cold)

At least that's what I've been told. Speaking from my personal experience though, the 80% hydration dough with 20% flour used in tang zhong does look like a 60% hydration dough, but it behave like a dough of somewhere between 70-75% hydration to me since it will be more sticky (due to gelatinized starch) and quite more extendable than that of a 60% dough, but definitely not a slack dough like normal 80% dough either.

Now, from your response, am I wrong to assume that I should count ingredients that soak up the fluid as part of the over all flour and based my hydration calculation from that? And in this case where I happened to weigh it before and after soak, those water should be added to the fluid side of the equation?

Every time lately when I have made a tanzhong or a scald, the dough has come out wetter than I expected. But it sounds like you have more experience than I do with it. It's probably hard to distinguish the gel aspects from the effect of water when the dough is already pasty instead of being like an ordinary elastic (mostly white) wheat dough.

I wouldn't say I'm that much experienced with Tang Zhong, to be frank. I started using it when it became a thing a few years ago without realizing that much of a difference in the dough, but I was just start making bread so I think it was partly me doing a lot of things wrong with the dough/not skilled enough to handle the dough. I still continue to use it though.

Just around half a year ago, I discover this YouTube Channel, and this is where I learn a lot more about Tang Zhong. They do a lot of scientific explanation of Tang Zhong. If you are interested, I recommended this video for the summary of everything to know on Tang Zhong. If you really are interested, they do scientific talk after most recipes and there are quite a lot of valuable tidbits there also. These were a very steep learning curve to me. It took me a few months with some trial and error to wrap my head around this technique. Possibly because, being self-taught in bread making, I was not skill enough to make an okay loaf before, until around the same time I start learning about their method of using Tang Zhong, so it was like learning to master the correct way of bread making I just understood, and introducing Tang Zhong into the mix at the same time.

I still cannot make head or tail with the Tang Zhong now though. To me, texture of bread using their method of Tang Zhong is quite different from the one without to the point it's almost comparing apple and orange. If I'm lowering the proportion of Tang Zhong, they would probably be much more similar and I might get the best of both world, but I'm quite hooked on this texture, especially when toasted, and I don't bake often, so I'm a bit reluctant to change it.

With all that said, and with my limited experience with Tang Zhong, the wetter dough might be the feeling you get from the stickiness of the gelatinized starch? Dough using Tang Zhong is extra sticky, it's even still a bit sticky after properly kneaded.

Here's a batch of Tang Zhong I've prepared. You can probably tell from its look that this thing is sticky, and it'll stay that way even when it is kneaded and dispersed throughout the dough, making the whole dough stickier with it:

TZ.jpg

Or if you mean the baked bread is wetter, that's probably because the gelatinized starch holding moisture within the bread, which is the whole reason people start using Tang Zhong in the first place. But, if the scald is big enough in proportion, it can get to a point where too much moisture is being hold inside the bread and you need to bake for longer just to drive it out or you get a gummy crumb. I've been there a few time when I realized this new proportion of Tang Zhong make the dough a lot easier to handle, so I went ham on the hydration. (As mentioned before, I used to use 5% Tang Zhong, so an 80% hydration dough is pretty much the slack dough it always have been and I get some what used to handling it. So, with new method making it handle much closer to 70% hydration, I can technically go up another 10-15% and still handle it. Boy, the gumminess I got back then is really something. I have to toasted them long before they crisp up and it didn't crisp quite well either. It also takes a lot longer to develop gluten. That's when I start to cut back down and find that somewhere around 75% is the sweet spot for me in terms of kneading time and result)

Let's see how your numbers compare with my recent bakes that used a scald or tangzghong.

1. 100% whole wheat sourdough. I sifted out the bran and scalded it. Total liquid was 81g water in scald + 195g, total flour not counting scalded bran = 300g. This gives 92% hydration. The scald weight was 36% of flour. Scald flour baker's percent was 9.3%. The dough without scald (65% hydration) was very much like a paste at first but with a rest it became more like a normal dough. After I worked the scald in, and after another rest, the dough started to develop some gluten, judging from the feel. Eventually I was able to proof the loaf free-standing.

2. Japanese milk bread. The tangzhong used 27.5g AP flour with 138g milk = 165g. Total loaf flour was 432g. So the tangzhong weighed 38% of the flour. Including its water, the hydration was 85%. The flour in the tangzhong was 6.4% (baker's percent). Hydration without counting the milk in the tangzhong was 53%. Of course, there was a lot of butter worked in also.

Summarizing the baker's percentages:

You wrote "I used to use 5% Tang Zhong". What do you use now?

So, first of all, I'll have to admit my fault in assume that scalding was interchangeable with tang zhong. I vaguely know it's a involving mixing hot water with some part of the flour which should result in gelatinized starch like tang zhong, so it wouldn't be much different, or so I assumed. As soon as you mentioned the 'scalded bran', I knew I was very wrong about my assumption and this is unchartered territory for me.

Now let me address the milk bread first as it is more familiar to me. I assume you are using the tang zhong 1:5 method as the number work out to be about that (138 is about 5 times rounding of 27.5). That's the 5% tang zhong I said I 'used to use' (or to be exact, 6.4% tang zhong in this case). So, in my view, I will still count it as a 85% hydration dough since water (or milk) use in tang zhong still count toward the total hydration of the dough as normal. The difference will be in how it look and behave. From 85, we use 6.4% of the flour in tang zhong, and it get at least the same amount of water, this 6.4 is properly gelatinized, so the the dough would look like an 85 minus 6.4 which equals to 78.4% hydration dough. It would be a bit stickier and more elastic that normal 78.4% dough, although not by much, probably behaving like 81-82% hydration dough. That's the reason why I said 5% tang zhong doesn't make much of a differences.

Now, back to the whole wheat loaf. After some more thought, If I understand correctly, you mean that 9.3%, or 27.9g, is the weight of flour in scald excluding the bran, right? If that's correct, that's 9.3% tang zhong in my book. So, the dough should behave like 92-9.3 = 82.7% hydration dough in my book. Then again, if I understand correctly, there is also scalded bran of unknow weight here, correct? Not sure how many gram that would be, but that would soak some water up as well since normally whole wheat flour will take more water than white flour because of the bran. And there is a possibility that scalding it might help it retain water better by some underlying mechanism, maybe? Since I was using oat in this recipe, I also just learned that soaking oatmeal in hot water and making oat porridge out of it work in pretty much the same way as tang zhong when the starch in the oat and pentosan hold onto that water. So, there's some unknown variable to me here.

Back to what percentage of tang zhong I'm using these day, it's 20% as default. And by tang zhong, I have to admit using it out of habit, but they are widely called yudane. In the view of the YouTuber I mentioned before, she traced back and found some research mentioning that Tang Zhong and Yudane is technique centering around using gelatinized starch in the dough regardless to the method used to gel it, be it cooking on stove top or pour boiling water onto it, and regardless of proportion of flour to water. Also, Tang Zhong/Yudane writes the same in Han Zi and Kanji, just pronounced differently in different language (Chinese vs Japanese). It started in Japan as Yudane, and when a Taiwanese baker pick it up, they read the same character as Tang Zhong. It later is popularized from the Taiwanese baker who use a cooking on stove top method with 1:5 ratio, so the world knows it as Tang Zhong. On the other hand, Yudane got introduced as a Japanese method that use a 1:1 ratio of boiling water pouring over the flour, much like a scald and hence my confusion.

To make this more clear, my number would be as following: For a 100g dough with 75% hydration and using 20% Tang Zhong, I take 20g of the flour from the 100g and dump it on at least 20g of boiling water. Flour clumps up very easily doing it the other way around, so I tend toward using 1:2 ratio when recipe allow as it is much easier to mix and maintain proper temperature for gelling during the process (65C, if I'm not wrong) so, 40g here. That leave me with 80g of flour and 35g of water in the main dough. It's still a 75% hydration in my book and not 35%, but look and behave somewhere around 60-65% dough. The crumb texture of this 20% tang zhong bread is what I mentioned as quite different from bread without it to me. Also, I just started using rice flour in tang zhong recently (by the introduction of the same YouTuber). Rice starch is different from wheat starch and when gelatinized and it help improve crumb texture and rise. Although, its crumb is a bit different from straight wheat flour tang zhong also, and it also introduce steam rice flavor to the dough; but that's another story altogether.

Now, back to the whole wheat loaf. After some more thought, If I understand correctly, you mean that 9.3%, or 27.9g, is the weight of flour in scald excluding the bran, right?

Actually, I only scalded the bran. There was no flour in the scald.

So, the whole 27.9g is bran? that's a whole new territory to me now. As I mentioned though; those bran normally soak up some water, and maybe it might do it even better after scalded?

Yes, that's been my experience.

Here's the crumb:

S__14139435.jpg

So, I think it should be a good idea to start from scaling up this working proportion first to my desired amount. But then, it looks like it can be a very large loaf that I'm a bit concern it can be too large for my tiny oven. Then it hits me. If too high hydration seems to be my problem since more water is introduced through soaker water, why don't I just cut down on that?

So, my new questions are:

1. What would happen if I cut down the soaker water and leave it not fully hydrated? I supposed it should suck up hydration from the bread by itself during bulk ferment and everything would even out overtime, right? It wouldn't result in spots of unevenly hydrated bread, would it?

2. Or, if fully hydrate the seeds and oat will be more ideal, would using milk to soak them be a problem? I haven't dial in the number, but I supposed, at most, only the oat would have to be soaked with milk and not the seeds, which sounds like it shouldn't be a problem, should it?

Since I always find interesting things kept inside this forum despite it being a thread from 1, 5, or even 10 years ago; I'll document the experiment loafs I tried after this one and the final (but flawed) loaf here along with my observation, in case someone might find themselves wondering something related to this in the future.

Second attempt

So, after the first attempt, I suspect the oat might hold onto too much water and make my dough too watery to hold shape. To test that, I experimented with only flaxseed and sesame that I still have on hand (no more surplus oats, sunflower seeds, and pumpkin seed), but increase their proportion to substitute for the missing ingredients. Turns out, flax and sesame can also soak up water well at the 150% rate of their weight. (40g dry of 50/50 seeds comes up to 100g after soaked and drained). The resulting loaf, unsurprisingly, has the same consistency as the first attempt. I tried to give it more time and used a gentler approach with stretch & fold every 15-30 minutes instead. After a few rounds of fold, the dough looked to develop some more substantial gluten, but tear up miserably once I got it outside of the bowl and tried to do anything with it, so I add the same proportion of flour to it and after 5-10 minutes of slap & fold, the gluten developed well. The loaf didn't hold shape as well as the first attempt and came out a lot flatter. At first I chalked it up to my shaping technique since I didn't give it as much effort, but in retrospect, after learning about flaxseed gelling effect and its (quasi-?)emulsion attribute and the slimy feel in the watery dough, which is also apparent, even more so, in the first attempt although I blamed it on the oats, I suspect this might have also affect the dough as well.

Third attempt

Suspecting that the hydration was too high, I thought I'll try cutting the water down by using part of the water in the original recipe to soak the seeds as well. Tired of toasting two kinds of seeds, I just used straight flax this time as I have more of it, and something interesting happened. In the first two attempts, flax were toasted rather early and they have time to cool down before the soak. This time it was just out of the pan when I pour water over it and they crackled rapidly. I did not think anything of it, but after 30-60 minutes when I came back, all the water added had gelled up almost like a glistening solid seeds jelly. I can see more gluten development this time around, though not by much, since I start to feel sick of flaxseed at that point, I didn't bother adding more flour, scraped that dough away, and just concluded that without the added flour, the flour proportion was too low and there is not enough gluten to hold all the seeds.

The actual attempt

From all the observation so far, I came up that I would both add the same proportion of flour and replacing some soaking water with the milk in the recipe to cut down hydration. That proved to be a very wrong thinking of me. The dough turned out very dry. It behave like a dough with somewhere around 55%. I really had to worked it hard and that affected the seeds inside also. The gluten development was not very great. I worked it until I kind of get some window pane, but the dough showed sign of tearing during bulk. It puffed up in the end, but there was pretty much no oven spring at all. The dough turned out to be an okay dough, but compare to the original recipe, or even the first test attempt, it was relatively a disappointing dough. The crumb is denser and drier than it should have been.

In retrospect, the fault was on me.

First, adding flour already worked in the first attempt, but I was worried that it was at 90% hydration, and dropped it down to 75% in one go just to make it closer to the hydration of the original recipe.

Second, in that mean time, I learned that oat porridge could act in the same way as Tang Zhong, so I used hot water this time to make proper porridge and it really soaked up all the water along with the rest of the warm milk I subsequently add when I see that it can soak up more. I should have realized that this would effectively make the dough drier than the first attempt that I cold soak them.

Third, making proper porridge make the oat release pentosan, which would interfere with gluten development.

So it was unsurprising, in retrospect, that the dough turned out that way.

What I'll try next would be: I might add back all or at least half of the cut out hydration and maybe hold off the added flour on the side and see how things go with the porridge because the porridge should help make the dough more manageable just like additional tang zhong, and all the pentosan will require additional water. I'd pound flaxseed to crack them and all seeds would be treated to a hot soak as well to just get the gelling going. My thinking is that it would probably be better this way than let it happen later not knowing when, maybe? Also, I'll try hold off the seeds and fold them in in before bulk instead, that should make everything easier.

Also, just for my curiosity, I'll try a small roll replacing the whole seed and oat portion with sesame since it might not hold onto water as well as flax and oat, or even if it is, shouldn't interfere with gluten development. This should settle if the original recipe can develop enough gluten to hold all the seeds. Also, I think I can eat sesame bread all day any day, unlike flax.