I am far from a sourdough expert. I’ve only been baking sourdough since February, and I still have a lot to learn about shaping, scoring and proofing to perfection.

However, there is one thing I have learned well: how to squeeze more flavor out of my naturally sweet starter. Here's the basic tips.

1) Keep the starter stiff

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye

3) Use starter that is well-fed

4) Keep the dough cool

5) Extend the rise by degassing

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge

Photos and elaboration follow.

It’s a common lament that I see on bread baking forums – Why isn’t my sourdough sour?

Personally, I blame Watertown. My evidence? I gave some of my starter to a friend who lives six miles away in Lexington. Within 6 weeks, she was making sour tasting sourdough. Her local yeastie beasties are clearly more sour than mine.

I don’t know what it is about the microflora that live in the little hollow between the hills that I occupy in Watertown, Mass., but treated traditionally, my white starter and my whole wheat starter pack as much sour taste as a loaf of Wonder Bread. That’s not to say that the loaves don’t taste nice. They do. They’re wheaty with a touch of a buttery aftertaste.

But they don’t taste sour, which is how I think sourdough ought to taste.

Anyway, I’ve finally figured out how to get the tangy loaves I love. If you’re facing the same sweet trouble as me, perhaps some (or all) of these tips will help.

1) Keep your starter stiff:

Traditionally, sourdough starter is kept as a batter. The most common consistency is to have equal weights of water and flour, also known as 100% hydration because the water weight is equal to 100% of the flour weight. That’s roughly 1 scant cup of flour to about ½ cup of water. Jeffrey Hammelman keeps his at 125%, and quite a few folks keep theirs at 200% (1 cup water to 1 cup flour).

I keep my sourdough starter at 50% hydration, meaning that for every 2 units of flour weight, I add 1 unit of water.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

There are two basic types of bacteria that flourish in a sourdough starter. One produces lactic acid, which gives the bread a smooth taste, sort of like yogurt. It does best in wet, warm environment. The other makes acetic acid, the acid that gives bread its sharp tang. These bacteria prefer a drier, cooler environment.

(Or so I've read, anyway. I ain't no biochemist; I just know what they print in them books.)

A hydration of 50% is pretty stiff, especially for a whole-wheat starter. You really have to knead strongly to convince the starter to incorporate all the flour.

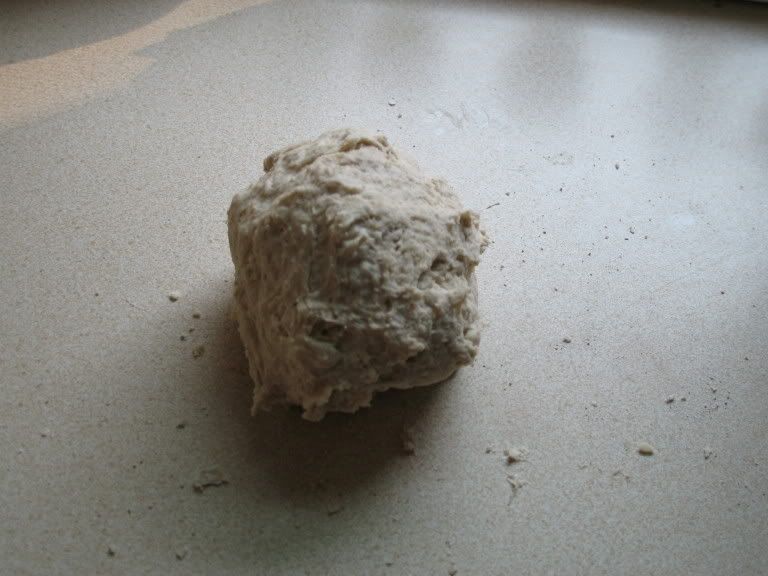

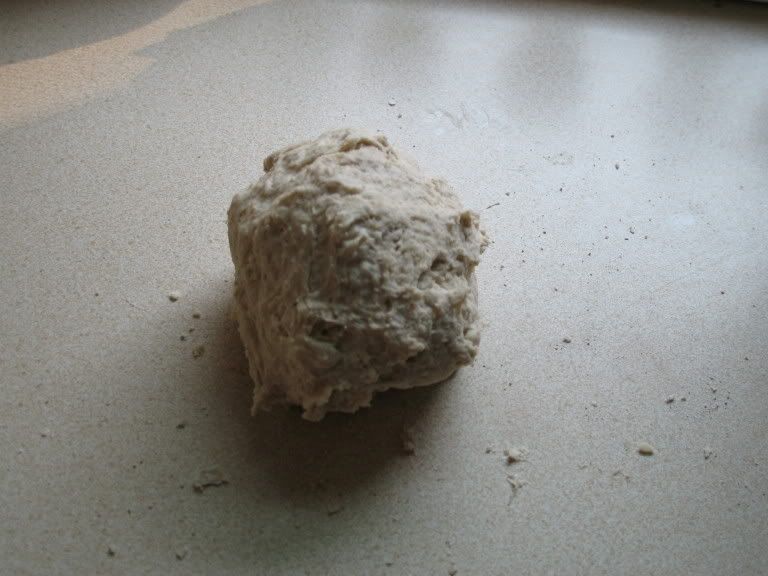

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

Conversion from 100% to 50% isn't hard to do if you've got a kitchen scale.

Take 2 ounces of your 100% starter. Then add 5 ounces of flour and 2 ounces of water. This should give you 9 ounces of starter. Leave it overnight, and it should be ripened in the morning.

From there on out when you feed it, add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. I'd recommend feeding it 2 or 3 more times before using it, though, so that the yeast and bacteria can acclimate to the new environment.

There are additional advantages to a stiff starter beyond producing a more sour bread.

First, a stiff starter is easier to transport. Just throw a hunk into a bag, and you’re done.

Supposedly, the stiff stuff keeps longer than the batters. You can leave stiff starter in the fridge for months, or so I hear, and it can still be revived. Never tried it myself, though, so don't take my word for it.

Finally, the math for feeding is easy at 50% hydration, much easier than 60% or 65%. Just feed your starter in multiples of threes. For exmaple, if I’ve got 3 ounces of starter and I need to feed it, I'll probably triple it in size. To get six additional ounces for food, I just add 4 ounces flour and 2 ounces water. Piece of cake.

Converting recipes isn’t hard either. First, figure out the total water weight and total flour weight in the original recipe, including what's in the starter. If the recipe calls for a 100% hydration starter, then half of the starter is flour and the other half is water. Divide it accordingly to get the total flour and total water weights in the final dough.

Now, add the total water and total flour together. Take that figure and multiply by 0.30. This will tell you how much stiff starter you’ll need.

Last, subtract the amount of water in the stiff starter from the total water in the final dough, and the amount of flour in the stiff starter from the total flour in the final dough. The results tell you how much flour and water to add to the starter to get the final dough. Everything else remains the same.

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye flour:

It doesn’t take much. Currently, my white starter is about 10-15% whole rye. Basically, for every 3 ounces of white flour that I feed the starter, I replace ½ ounce with whole rye. That small portion of rye makes a big difference in flavor. Rye is to sourdough microflora as spinach is to Popeye. It’s super-food that’s easily digestible and nutrient rich. That’s why so many recipes for getting a starter going from scratch suggest you start with whole rye.

Here I am, about to add rye to "Barney Barm," my white starter. I haven’t added rye to my whole-wheat starter, though. It hasn’t needed it – there’s more than enough nutrients in the whole wheat to keep the starter party going strong.

3) Use starter that is well fed: Early in my search to sour my sourdough, I’d read that, if you leave a starter unfed and on the counter for a few days before baking, it will make your bread more sour.

I’ve found that’s not the case. The starter gets more sour, but the bread doesn’t taste very sour at all.

The better course is to take your starter out of the fridge at least a couple of days before you use it, and then feed it two or three times before you make the final dough. Healthy microflora make a more flavorful bread.

4) Keep the dough cool:

When I first started out, I was following recipes that called for the dough to be at 79 degrees, and I’d often put it in a fairly warm place to rise. Warmth kills sour taste. Nowadays, I add water that’s room temperature, not warmed, and aim for a much cooler rise, no higher than 75 degrees and often as low as 64.

The cellar is your friend.

5) Extend the rise by degassing:

When I make whole wheat sourdough, I usually let the dough rise until it has doubled and then degass it by folding until it rises a second time. Along with cool dough, this means the bulk fermentation usually lasts 5-6 hours.

When I’m making pain au levain or some other white flour sourdough, I usually have the dough very wet, so it needs more than one fold to give it the strength it needs. In this case, I fold once at 90 minutes and then again after another 90 minutes. Usually, the full bulk rise lasts about 5 hours.

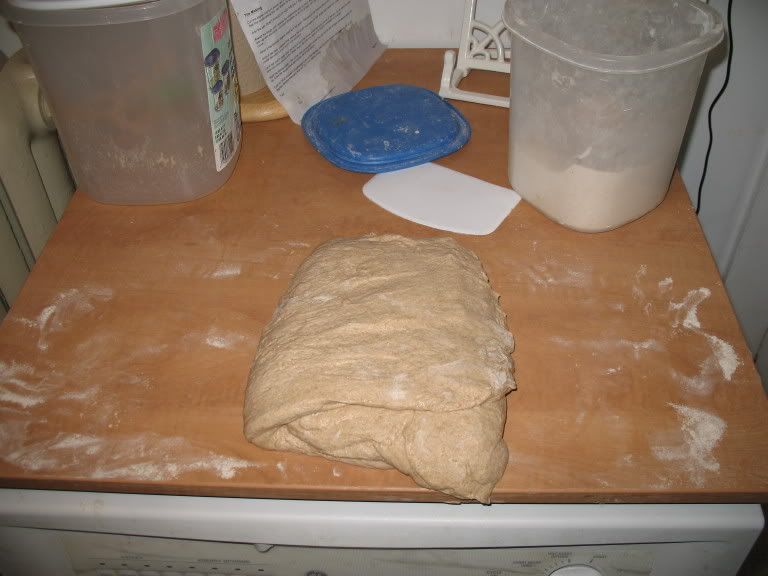

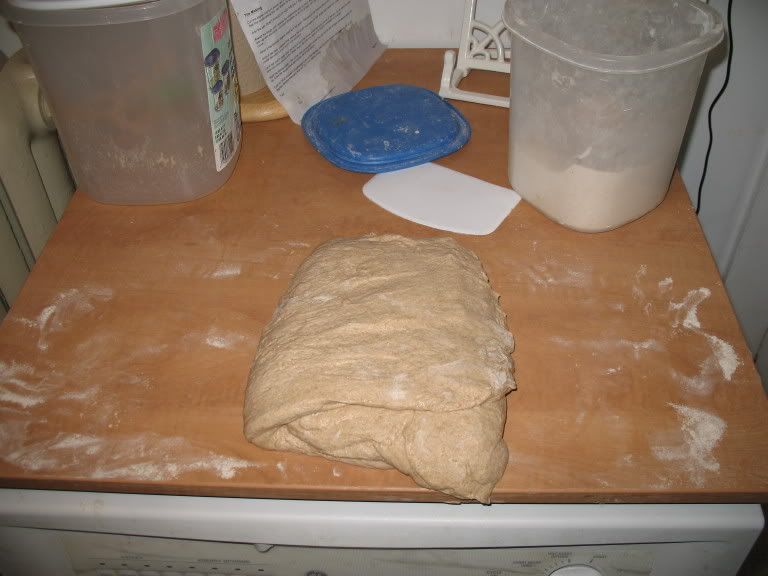

Here's a sequence showing how I fold my whole-wheat sourdough.

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge:

This final touch really brings out the flavor. So much so that, if you’ve incorporated all the other suggestions, proofing overnight might make your bread a bit too sour for your taste. My wife and I like it assertively sour, however, so this step is a must.

Normally, I’d suggest proofing your loaves on the top shelf where it’s warmest, so as not to kill off any yeast, but I find that if I put my loaves in the top, they’re ready in about 4-6 hours, at which time I’m usually sound asleep. So I started putting them in the bottom, and had better luck.

I hope this helps those of you who dread pulling another beautiful loaf from the oven, only to find it looks better than it tastes. Best of luck!

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white. For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit. Here's what it looks like after kneading.

Here's what it looks like after kneading. And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet). Stretch it to about twice its length.

Stretch it to about twice its length. Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal. Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.