More sour taste in my sourdough loaf?

I'm new here and did a search on the above topic, with lots of advice and discussion available, but wonder if anyone would be so kind to give me specific direction?

I'm wish to obtain a much more sour taste.

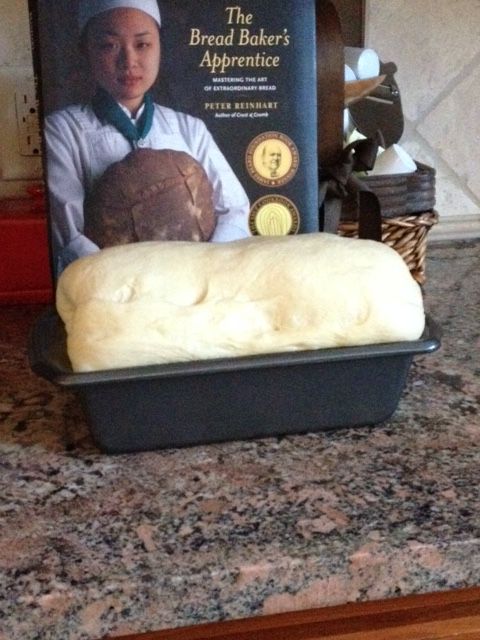

Below is the recipe I used and pictures of the loaf, it really came out great but no sour taste whatsoever. A very light, soft and fluffy bread.

Starter was made using Reinhart's method with whole wheat flour and pineapple juice, then switching to water and King Arthur Bread Flower.

1.) Fed the starter and waited until it tripled in volume, then stirred it back and used a 1/4 cup.

2.) Recipe as follows:

Sams Club bread flour bleached - 500 grams

Whole milk - 300 grams

Sugar - 24 grams

Salt - 10 grams

Olive Oil - 24 grams

Lecithin - 1 teaspoon

Vital wheat gluten - 2 tablespoons

Ginger powder - 1/4 teaspoon

Ascorbic acid - 1/8 teaspoon

Starter as above 1/4 cup.

Mixed everything in a Kitchen Aid with dough hook for about 15 minutes, excluding the salt.

Added the salt and mixed for another 5 minutes.

Closed with wrap in a container and let it rise for 18 hours.

De gassed, folded, into oiled bread pan, covered with wrap and let it rise for 10 hours.

Into the oven 400 F then down to 340F total of 40 minutes.

Great bread but no sour whatsoever? Is there an easy tweak I can do with the recipe, or do I start over?

The first bread I baked with this starter, I used 1 cup of starter and only a single 18 hour rise. It had a very slight tint of sour, but still nowhere near sour, so I am wondering if I should just use perhaps 1 1/2 cups of starter and try again.

Thanks for any advice.

I would look for a bread that is made with flour, water, starter and salt. These are the ingredients used to make sour sourdough breads. You want a long slow cool process not a fast warm process. The recipe you used reads more like a cake recipe than a bread recipe.

Jeff

Why all the additives? Sourdough is a natural dough conditioner.

You have the loaf pictured in front of BBA -- is that where you got the formula? Does Peter say that it is supposed to produce a sour loaf?

I think of sweet and sour as being on opposite ends of the spectrum, and hence, I would not think that adding sugar can do anything to enhance the sour.

Did you know that you lose half of your taste receptors by the time you are 20? That is very sad, but maybe that is why our tastes change over time and things we once disliked become more palatable as we get older.

I worked up to a very soft and fluffy white sandwich loaf, tweaking until I got the texture and shelf life I needed, using normal instant yeast. The Costco flour is a little low in Gluten, hence the vital wheat gluten.

So, in short I thought I would use the exact recipe with my starter instead of instant yeast.

The result was close, this one is a bit more chewy, but very light and soft. Takes forever though. I was chasing sour, did not get it.

I will try Reinhart's recipe next doing exactly what he wrote and see what happens.

Sorry I meant Sams Club flour, not Costco.

I think the BBA is there to show that he used the pineapple starter method Reinhart now supports (the one from Debra Wink). That is a great way to make starter. I am also wondering why the starter is 1/4 cup and the rest is in grams. Everything should be by weight or it is hard to tell how much starter you are using percentage wise.

On to the question at hand. First, that seems like a very long time to have the dough on the counter. If this was in the refrigerator during some of it, then that would make more sense. Second try out a more lean dough (i.e. without the extra stuff) as mentioned above. Third, the addition of some rye helps with the sour.

To me, the key is to refrigerate during most of the proofing. A nice overnight proof in the cold helps to get the flavor you are looking for. I like to add rye as well because it helps make it even more sour. Try out Hamelman's Vermont Sourdough With Increased Whole Grain. Since you have a 100% hydration starter, you can just use the re-calculated formula posted here:

http://www.wildyeastblog.com/2008/11/05/more-sour-sourdough/

Thanks for the advice, I will give that a shot.

You are right, the starter should be in grams, I took a short cut due to the messy nature of the stuff and getting it on the scale.

The proofing was in my kitchen, on the counter closed with plastic wrap at around 74F. It rises really slow and I have to leave home for work, so the time intervals worked out really well for this one.

What Rye are you using, the normal at the Supermarket, or do I have to get from Amazon?

Hope this helps...

When weighing starter, don't put it on the scale. Put a bowl or other vessel on the scale, hit the tare button to zero it out and then add the starter to the bowl and you have the weight of your starter without messing up your scale. If you don't have a tare function, weigh the vessel, add how much starter weight you need, and then add the starter till you get to the right weight.

Alternatively, do the reverse. Put your starter container on the scale, zero it out. Now remove enough starter so that the scale reading will go negative and tell you how much starter you removed. Then just make sure you get all the starter off of your spoon and you are good to go.

Just the normal supermarket rye works fine.

Maverick, for the recipe posted, is it best to feed the starter before, or not?

From the information below, it appears as if the starter out of the refrigerator (5 days) without feeding may produce more of a sour effect?

at room temperatures for bulk fermenting and final proof, then you want to ge the LAB numbers up dramatically in the starter while keeping the yeast numbers as low as possible at the same time. A normal SD starter has about 100 times more LAB than yeast in it. With more LAB and fewer yeast it will take longer to ferment and proof because of the low yeast numbers while giving more time for the extra LAB to reproduce and more LAB with proper food means more sour.

The two best ways to increase LAB while limiting the yeast is to use Whole grain flours for the starter (Rye and WW or a mix of the two) and to keep the starter retarded for a very long time at 36 F. At this temperature LAB out reproduce yeast at a rate of 3 to 1 but both reproduce very slowly at those low temperatures so it takes a long, long time to get the LAB numbers up substantially while keeping the yeast numbers low.

I do a 3 stage build for a total of 100 g of 66% whole grain starter in the fridge for up to 16 weeks using a small amount of starter (6 g) to build a levain for a loaf of bead each week.The first 2 stages are 100% hydration,4 hours each, throwing nothing away and the levsin should double after the 2nd build. The 3rd build is where you thicken it up to 66% hydration and let it rise 25% in volume before refrigerating it. Here is a schedule where the size at the end depends on how much you bake. I make a loaf a week and use the lower or middle line

If this still doesn't get you the sour you want then you need to think temperature in the other direction 93F where LAB outproduce yeast 13 to 1. If you do your starter, levain and dough ferments and proofs at that temperature, or some combination, you LAB count as compared to yeast will go off the chart. IF you do them all, your bread will be too sour by far. I usually do the levain build only at that temperature using a heating pad and over that 12 hour period the LAB are numerous and the yeast restricted enough so that when they hit the dough the bread comes out just as sour as I want it, So I do starter very long cold retards and levain building at high temperature to get it just right in teh winter, In the summer I can skip the heating pad since my kitchen temperature in AZ is almost 93 F anyway

Happy Baking

PS. I also do long old retard of the shaped dough for a final proof year round as well.

Thx, that was very helpful. Your technique will be my next adventure. :-)

You can also experiment with using a firm starter. Converting to firm is not the same thing. It takes a week or so for things to develop. I much prefer the ease of mixing at 100% hydration, but have done the firm starter before to change the flavor profile to be more sour. Now I rely more on retardation of the final dough.

By this, do you mean, the ease of measuring out the water and knowing that you need an equal measure of flour?

I've been using the 80% hydration that Forkish recommends lately, and it was driving me crazy to get the math right. Finally I decided to use the bakers% app on my iphone to create an "80% hydration starter" formula (i.e., 10 grams flour, 8 grams water) so that if I need to create 30 grams of new starter I just change the "bread weight" to 300 grams and it tells me that I need 167 grams flour and 133 grams of water.

The trouble is, the App rounds so that if I wanted 30 grams of new starter, it tells me to add 17 grams of flour and 13 grams of water, which is a hydration of 76% not 80%. So... to get it right I need to tell it 300 grams and then move the decimal over so I am using 16.7 grams flour and 13.3 grams of water...which is a bit of a headache and makes me wonder if 76% vs 80% really matters, and b) if it does, whether 80% hydration starter is really worth the headache!

Math is easy for me (see below). I just didn't like the process of mixing up a firm dough and cleaning up afterwards compared to the batter type. Plus I found it harder to read the firm dough since I am so in tune with the 100% hydration ones. I never tried 80% and that might be okay to work with. I also never went down to 50% which also might be okay to work with. I have tried both 66.67% (i.e. 2/3) and 60%. A firmer dough will produce more acetic acid than a higher hydration one. But if you go too firm then everything slows down and the flavor profile is not what I look for. This is why I didn't go to 50% which seemed too dry in my mind (could be wrong). But 80% might not be too bad and I might try that in the future.

The math part isn't very hard. If you know how much you want to make, just divide that by 1.8 (for an 80% hydration starter) and that will tell you how much flour. Subtract to get the water. So in your example if you want 30g of starter then 30/1.8=16.667g of flour. 30-16.667=13.333g of water. Of course I would probably make it easier on myself and just make 45g starter and discard any extra if needed (25g flour, 20g water) or maybe I would do 36g starter (20g flour, 16g water) if I didn't want to be wasteful. The principle holds for any percentage starter you are trying. So a 60% hydration means divide by 1.6, 50% means divide by 1.5, etc.

I also have no problem converting recipes that call for different hydration starters. As long as you think of it as the percentage of flour coming from the pre-ferment (starter in this case) rather than simply the percentage of pre-ferment, the adjustments are easy. I even have an Excel spreadsheet I put together to make it easier.

To answer your pondering, a) for a starter I would not sweat that difference, b) If the only "headache" is the math then hopefully my explanation above will help. For 80% hydration starter, it might also help to keep the total starter weight divisible by 9 to avoid decimals.

At least, it is harder than measuring equal amounts of flour and water. Having to divide by 1.8 means I have to use a calculator and my hands aren't usually all that clean when I am doing baker's math. :)

I do very much like the idea of keeping the starter weight divisible by 9 to avoid decimals. That is quite clever. And it is super easy to get numbers divisible by nine since if the sum of all digits is divisible by nine, then it is divisible by 9. Need 371 grams of starter? Digits add to 11, need 7 grams more to make it divisible by 9 so that means 378 grams of starter (divided by 9 = 42 grams flour, 336 grams water).

Thanks for that!

Calulators? We don't need no stinkin' calculators!

You mentioned using an app, so I figured you were using electronics to plan ahead. If you want to do this in your head (or quickly on paper), then multiply by 5/9 to get the flour. If you keep it divisibly by 9 like discussed then the math is easy because you divide by 9, then multiply by 5. Both those numbers are fairly easy to work with for most people. So like you said, make it 378g instead of 371, then divide by 9 to get 42 and multiply by 5 to get 210g of flour and 168g of water. You just missed a step above unless you want 800% hydration.

I never said the math was as easy as 100% hydration. I just meant it wouldn't be a factor for me when choosing the hydration of my starter.

Enjoy.

That is not my strong suit, but I can attest to the fact that failing to do so has on more than one occasion required me to spend more time fixing errors that could have been avoided.

I've just taken to writing in my books, for scaling formula so I don't have to do it in my head or with my dirty hands and my phone. I do like the app as it is free, and lets me enter a formula and scale it as I like, though I usually just use it to feed my 80% starter. :)

that less hydration, stiff, means a more sour starter. Everything I have seen says that LABs and yeast both love the wet. LABs more than yeast though, and replicate faster in a more liquid environment as long as they have food? The reason I keep a stiff starter is that I want o make sure it stays in control and doesn't eat all of its food too quickly over the long cold weeks it is in the fridge. At a higher hydration the food would be gone much more quickly and it would need maintenance way more often. What makes my starter sour is the very, very long time is it at 36 F not its low hydration. Since replication is so low at low temps, it takes a really long time to get it sour.

Let me try to explain (I am no Debra Wink). There are both homofermentative and heterofermentative LABs (as well as those that can switch between the two depending on the sugar consumed, etc). The homofermentative produce lactic acid only. The heterofermentative produce both lactic acid and acetic acid (along with CO2 and sometimes alcohol depending on the environment). Acetic acid is what gives the San Francisco Sourdough type of sour. So to get more sour, one would want to favor acetic acid production.

While you are correct that all LABs favor warm, wet conditions, it also favors lactic acid and alcohol production. That is to say the homofermentative LABs will be happily making lactic acid, and the heterofermentative LABs will continue making lactic acid and CO2, but will be more likely to make ethanol rather than acetic acid (the fermentation process will make one or the other, not both at the same time).

As you state, lower temperature results in more acetic acid. This has more to do with the reaction yeast have to the cold compared to LABs which indirectly influences the kind of sugar more readily available and therefore the push towards acetic acid production from the heterofermentative LABs. So if lowering LAB activity relative to yeast activity results in more acetic acid production, then lowering the hydration of the dough can offer the same benefits.

You say the reason for the sour is because of the cold temperature, but I would say that both the cold and the lower hydration play a part. For those of us that keep the starter on the counter, a stiff starter is an option when looking for more sour. This is also why converting to a stiff starter at the last minute (or vice-versa) does not have the same affect. It takes time for everything to equalize and the right species and activity to dominate.

Of course this still leaves the question of how low a hydration is optimal and whether we should be worried more about the profile of our starter or that of our final dough.

Hope that makes sense.

Edit to make a quick correction.

that are abundant in the beginning couple of days when making a new starter, replaced by heterofermentative LABs as the pH goes down and the culture matures to a stable starter of LAB and yeast that like to live together in a symbiotic lower pH environment at 7 days?

LABs only produce alcohol when the fructose is used up. There is only 1-2 % fructose in flour but as luck would have it, the yeast break down more complex sugars releasing fructose as byproduct for the LAB. LABs primarily make lactic acid, some acetic acid and a bit of CO2 and ethanol if and when the environment allows it. The vast majority of the CO2 to nmake the dough rise and ethanol come from the yeast.

High and low temperature just allows LABs to out reproduce the yeast meaning that your starter and leavains can have more LABs and fewer yeast than normal. The only thing this means is that, no matter what temperature you develop and ferment your dough at , the resulting bread will be more sour because it is being inoculated with more LAB that make sour than normal and the yeast population is less than normal meaning it will take longer to ferment and proof the dough allowing the abundant LAB even more time than normal to make much more acid and sour taste than would otherwise be possible.

Assuming there is enough food, it is the temperature that is key and luckily easy to control so that we can make what ever amount of sour we want in the final bread. I look at the whole grain flours as a gardener would look at fertilizer. Whole grains just makes things grow a bit faster in my book and when the temps are low and you are trying to get LABs to reproduce at 3 times the yeast rate an little fertilizer in whole grains really makes a difference.

I canlt find any research on how hydration of 100% or 66% effects LAB reproduction and acid production other than a general statement that higher hydration with enough food the faster reproduction takes place - low hydration mean less reproduction but it is all relative too.

I am not saying that low temperature does not add to the sour. Just that lower hydration also causes more acetic acid production for the same reason. I disagree that high temperature creates the same result. Just because there is food that contains fructose does not mean it is always free. High temperatures favors ethanol production as the sugars are used up faster. The same can be said of wetter conditions if speaking relative to drier ones. Now if we are specifically talking about L. sanfranciscensis then all bets are off. This LAB is different than the norm and I can't speak about it with the same generalities.

Here is a good read I just found while trying to answer about research:

http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/10375/lactic-acid-fermentation-sourdough

i agree that removing most of the additives especially sugar, lecithin and ascorbic acid as these are both going to make the dough more like commercial bread (fast) production.If you were really after a sour taste with this recipe simply allow the milk to sour before using.

From your pics which are great and can help with diagnosis, the dough seems to be fully proofed, and the baked loaf shows no kick or oven spring that confirms that suspicion,The colour also gives a hint that it is a little spent too, there is also some mottling or slight different colour blotches on the loaf, this is often indicative of salt not being evenly distributed, and i note that you added this sometime later, and although mixed for a further 5 minutes may not have completely dissolved or assimilated into the dough.

There are two mouse holes that have formed under the crust, these are sometimes the result of an excess of dusting flour or oil that keeps two folds of dough apart and allows a pool of gas to form,

I do concur with other posters that a longer cold fermentation will most likely help with the quest for a more sour taste experience, Dab has put forwarda method of obtaining a better sour, i have found that neglect of the starter has often given me a similar rise in sourness, having forgotten a feed or two especially having left the starter out over the weekend at work and it missing four or five feeds in a row and then using the starter after a couple of restorative feeds has produced a much more sour result.

Anyway good luck and we look forward to future successes kind regards Derek

Thanks, I think your diagnoses from the pictures were very accurate. I read somewhere that it is best to add the salt after gluten development, which makes mixing a little more complicated.

Well, pretty much what dabrownman said. In a simpler statement, what has worked for me is a long slow first fermentation and a warm final rise.

However, over the years I have heard so many conflicting reports, some from experienced people, that I have come to the opinion that perhaps different starters respond differently or that there may be other things going on beyond that which a reporter illustrates in his comments.

Personally, I have never had much luck getting sour from a stiff starter, or any other great flavor for that matter. I tried off and on for several years to duplicate the prize wining loaf from PR's, Crust and Crumb that used a firm starter and failed to better liquid start while others that I trust claimed success..

Charles

Wrong!

Vinegar is acetic acid. The old-school S.F. sourdoughs got their tanginess from LABs, not from acetic acid or vinegar. We all know what vinegar tastes like and that's not the kind of sour the classic S.F. sourdoughs had, and is why I used the word "tanginess" instead of "sourness".

The last remaining "old-school" S.F. sourdough wasn't competitive back when the old-school bakeries were in operation and is frankly of poor quality. It has a distinct vinegary flavor because tourists on Fisherman's Wharf don't know the difference. Some on-line sleuths have suggested they may actually add vinegar. The flavor of old-school S.F. SD is unique; you don't know what it tastes like unless you've actually had it.