Trying for Flaky Scones, with flavor variations

Hello, I have some sharp cheddar to use - scones sounded good - I've been trying this way to make them.

These are a Cheddar variation - makes 12. Note I actually made 24 in this batch, which are pictured.

Ingredients:

2 cups (10 ounces) unbleached all-purpose flour

1 Tbsp baking powder

1/2 tsp kosher salt

5 Tbsp cold unsalted butter, cut into 1/2-inch cubes

1 cup heavy cream (I started with 208 grams which is a little less than 1 cup)

Half-and-half cream as needed

30 grams grated sharp cheddar

Method:

Place the flour, baking powder, and salt in the workbowl of a food processor fitted with the metal blade. Pulse a few times to combine.

Remove the cover of the food processor and distribute the butter evenly over the dry ingredients.

Cover and pulse 10 times. Mixture should be crumbly. Pulse a couple of more times if needed. Transfer mixture to a large mixing bowl.

Add the grated cheddar to the bowl, and mix in with your hands so all of the cheese is coated with flour.

Stir in the heavy cream and mix until clumps of dough form. I used a dough whisk for this:

I turned the clumpy part of the mixture out onto the counter. There's usually some dry bits underneath that haven't mixed in:

I stirred in a bit more half-and-half cream until more clumps formed then turned this out onto the counter too:

Using a bench scraper, I get underneath some of the dough and lift and press on top, to get the dough to come together. I do this from all sides, until it comes together into a dough ball. I try not to directly touch the dough, and press with the bench scraper, so I don't warm the dough up with my hands:

As I am making 24, I rolled the dough ball into a 10"x14" rectangle (using the bench scraper to push on the edges to even up the sides as needed); if you are making 12, roll to approximately 10"x7". I then did a business-letter turn with the dough:

And a second time (dough is getting smoother):

And a third:

A final roll to 10"x14", (10"x7" if only making 12), then divide into triangles (24 or 12 depending on how many you're making)(I don't do rounds because I prefer to not deal with scraps). I divide using the bench scraper, and am careful to keep the bench scraper vertical, that is, perpendicular to the counter, and to cut cleanly, straight down, and to not drag the bench scraper sideways. (I read somewhere this helps the scone to rise straight up):

I placed the shaped scones on a parchment-lined baking sheet (13"x18" because that's what will fit in my fridge), covered in plastic wrap, and chilled for 1-1/2 hours before baking.

One half hour before baking, (if making 24, consider whether you are baking on one big sheet or two smaller ones). Position oven rack(s) near the center of the oven. Heat oven to 425F.

Remove scones from fridge, remove plastic wrap.

If making 24 like I did in these pictures, transfer scones to one 15"x21" parchment-lined baking sheet or two 13"x18" parchment-lined baking sheets, to spread them out more/increase airflow around the scones so they bake properly, when baking all 24 at once.

Brush tops of scones with half-and-half. Place scones in oven.

Bake for 12-15 minutes (I baked these for the full 15 as they were well-chilled). Depending on how evenly your oven heats, you may want to rotate your baking sheets or move your scones around on the baking sheet partway through the bake, so they bake/brown evenly.

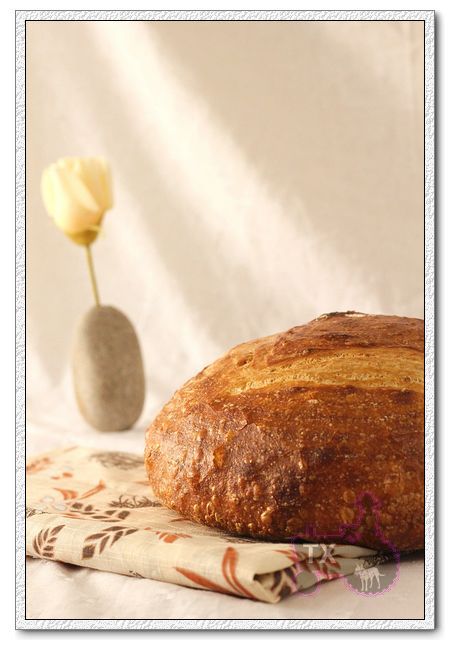

After 5 minutes in oven, after 10 minutes in oven, and the finished bake:

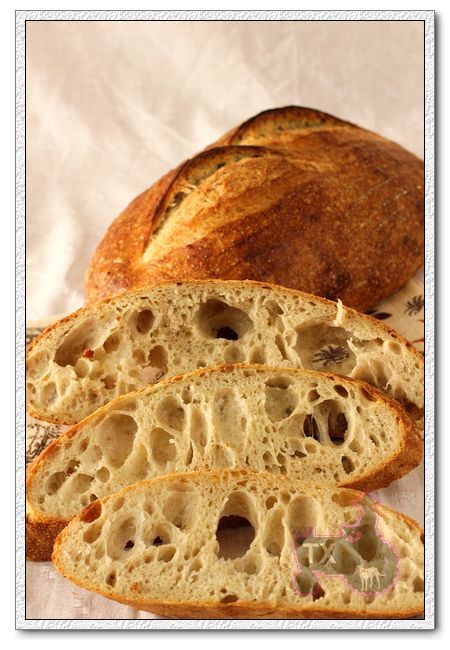

Somewhat flaky layers (some cheese melting out!) and a crumb shot:

These are an Irish Cream with Chocolate variation, with thanks to Neo-Homesteading's post! for a great idea!

This is what I tried for ingredients (makes 12):

Ingredients:

2 cups (10 ounces) unbleached all-purpose flour

1 Tbsp baking powder

1/2 tsp kosher salt

1/3 cup golden brown sugar

5 Tbsp cold unsalted butter, cut into 1/2-inch cubes

1/2 cup chocolate chips, pulsed in food processor until chopped up a bit (or you could use mini-chocolate chips)

1 cup heavy cream (I used a little more than 1 cup, 240 grams, as this is what I had left in my carton)

Half-and-half cream as needed

1-1/2 Tablespoons Whiskey (Irish if you've got it!) or Bailey's Irish Cream Liqueur

1/2 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

Turbinado sugar (for sprinkling)

I followed the same method as for the Cheddar variation above, except:

- added the brown sugar to the dry ingredients in the food processor at the start of mixing

- added the chocolate chips (not cheddar!) to the dry ingredients in the mixing bowl

- added the whiskey and vanilla extract along with the heavy cream to the dry ingredients in the mixing bowl

- after brushing the scones with half-and-half, I sprinkled them with Turbinado sugar, then baked.

I found this dough wetter due to the higher amount of heavy cream and Whiskey addition; I didn't have to add hardly any half-and-half to get all the dry ingredients to bind together.

The scones were browned at 12 minutes but I baked until 14 minutes as this dough was wetter. Depending on how your oven heats, you may want to turn some of the scones around partway through baking so they bake and brown evenly and don't get too dark in any one spot - this dough has a higher sugar content and it browns well. The aroma coming out of the oven was amazing while these were baking! :^)

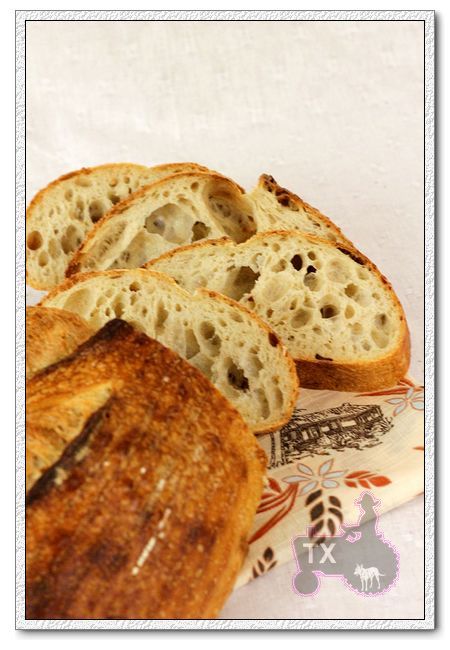

Here's a couple of pictures of the finished scones (the picture on the right with a small bit of glaze applied, made by mixing some icing sugar, 1 Tablespoon whiskey, 1 Tablespoon Bailey's Irish Cream Liqueur, a bit of half-and-half, and a tiny pinch of salt). The increased liquid did make these less flaky, so next time I will reduce the amount of heavy cream to that used for the cheddar scones, 208 grams, and see how it goes:

Happy baking everyone! from breadsong