The home milling and sifting adventure continues. My most recent effort felt like a big step forward in several ways. Tempering, based on some suggestions by proth5 in response to a previous blog entry, was explored. Multiple successively finer passes of the mill were used this time, including re-milling of the sifted results from various steps in the process. Home ash content tests were performed, to understand better the distribution of bran and outer seed coat particles across the various outputs of my milling process. The outputs were then blended to a desired ash content and a sourdough loaf was baked. Photos of the process are posted, as well as a video of the tempering system I rigged up at the last minute (this is more for entertainment, but it may have helped). A process flow chart is posted showing the steps followed to mill and sift this flour, as well as a spreadsheet showing the ash content analysis for the various outputs of the milling process.

Notes on the Bread

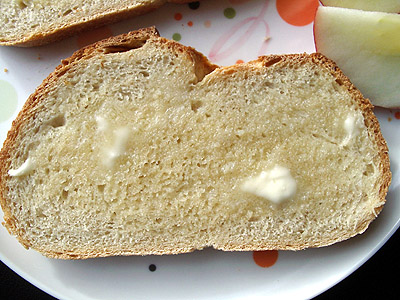

The recipe for the sourdough loaf is similar to that for previous blog entries except no whole wheat was used in the levain and the rye was lightly sifted through a #25 sieve to remove the larger bran particles. A levain was prepared with 15% fermented flour as a percentage of total flour in the dough. The rye flour was 5% of the total flour, and the remainder of the flour was the home milled and sifted blend from this adventure. The rye flour went into the levain. The hydration was 79%, which proved to be too high. I realize the water absorption is in between whole wheat and white flour, so I probably would have been happier with a hydration around 74%. The resulting dough was closer to a ciabatta dough than I was intending, but the bread that resulted was wonderful. I was using my brick oven for some braising earlier in the day, which forced me to refire the oven in an attempt to bring up the temperature. I mismanaged the heat a little, which caused the somewhat scorched bottoms of the loaves you see in the photos. The resulting bread had a much lighter crumb than previous attempts, showing that I was much more effective at separating out the dark from light components of the berry.

Tempering

Based on a great suggestion from proth5, I explored tempering the wheat berries before starting to mill. Proth5 added 2% water to the berries. Some discussion in "Wheat Flour Milling" by Posner and Hibbs suggested 14%-17% moisture content. A Delmhorst G7 Grain Moisture Meter was used on Heartland Mill "Milling Wheat (M2 product)" and found to have a 10.6% moisture content. I decided to split the recommendations of proth5 and the suggestions in "Wheat Flour Milling" and added enough water to the grain to bring the moisture content to 14%. In a later discussion with a representative of Meadows Mills (my mill is a Meadows 8 inch stone mill), 14% was considered a touch too high, and 13% was suggested as a reasonable moisture content for my mill. So, Proth5 suggestions were very good, but by then I had already added the water to the berries.

Concern for very even moisture distribution motivated a couple of strategies for tempering the wheat. First, an atomizer was used to spray the water a few grams at a time onto berries, stirring in between sprayings to initially do a good job spreading the water evenly throughout the grain. I then borrowed the rotisserie from my outdoor grill, and rigged it in my workshop to be able to mount a plastic container of grain on it. In order to rotate the grain for a few hours without putting undue strain on the rotisserie, it was counterbalanced by attaching some small, heavy vices on the counterweight, which was too small on its own. A video of the contraption is available, as it is hard to describe accurately, but easy to understand once you see the video. The rotisserie was used for a few hours until the wheat seemed fairly dry to the touch. It was then allowed to sit for about 30 hours before milling.

Multiple Pass Milling and Sifting

After reading some of the chapter on milling in "Wheat Flour Milling" and browsing through various diagrams of milling processes, I took a wild shot at doing what I could as a complete novice to approximate the processes in a general way with my Meadows 8 Inch Stone Mill, and a series of sieves stacked in a Sieve Shaker. The equipment is described in an earlier blog entry.

The basic idea was to first mill very coarsely to separate the bran gently from the rest of the berry, followed by sifting out the flour from the darker material, followed by re-milling and re-sifting the darker material to obtain more flour. True to the discussions in "Wheat Flour Milling", the whiter flour was extracted from the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th passes, not from the first pass. I was surprised to discover this, but the ash content results showed much lower ash content for passes 2-5, particularly for the flour extracted from 3rd and 4th passes.

Passes 1-4 were successive, meaning that the "coarse red material" sifted from the #40 or #60 sieve was re-milled and resifted in series. In pass 5 the coarser results of passes 2 and 4 were mixed, re-milled, and re-sifted. In pass 6 the very coarse, mostly bran output caught in a #40 sieve was re-milled and re-sifted.

A process flow chart is posted that shows the details of the milling and sifting procedure followed.

Ash Content and Blending

Six flours, two coarse red "products", and 1 "bran" were the final results of all the milling and sifting above. Home ash content tests were performed on all of those products, as well as on sample saved from some of the intermediate steps. A spreadsheet is posted showing the results of the ash content measurements.

The results show that the flour through a #60 sieve that looks very much like Heartland Mills Golden Buffalo has a very high ash content. It was the flour from passes 2,3,4, and 5 that went through a #60 sieve that ended up having lower ash content. The flour from pass 1 had an ash content of 1.4%, not that far from whole wheat. In earlier one or two pass attempts, the ash content was probably closer to 1.4%, which explains the almost whole wheat quality of the breads from my first two tries. The ash content of passes 2 and 5 was around 1%, a little lower than Golden Buffalo flour from Heartland Mill. The flour from passes 3 and 4 was lowest, around .7% and much closer to a white flour, which might be something like .55%.

In the spreadsheet I created blends of the various outputs, so that I could get the ash content desired. As it turns out, by combining all the "flours" and leaving out all the coarse red and bran products, an ash content around 1.1%, maybe a little lower but very comparable to Heartland Mill Golden Buffalo would be obtained. So, all the flours were blended to obtain the flour used in the bread pictured above. This bread was clearly lighter than previous attempts. The dough handled much more like white flour, created a satin smooth surface texture, and seemed strong and extensible. The yield was much higher than in previous attempts, 85% of the final products and 81.5% of the weight of the berries before tempering, yet the ash content was lower than flour obtained in previous attempts that only yielded around 65% of the initial weight of the berries.

Nutritional Editorial Comment

Sifting, as done here, does remove some of the bran, outer layers, and germ from the flour. However, since the ash content is around 1.1% and whole wheat is around 1.7%, it can be argued that around 2/3 of the outer layers is making it into this flour. So, although it is not a pure whole grain flour, it still has much of the material from the outer layers. By dusting the loaf with the bran, further fiber is added. As a results, this bread should contain a significant proportion of the nutritional benefits of freshly milled whole grain flour. For me, it's worth doing this to be able to enjoy breads with lighter flavors and textures closer to white flours, without much loss of the nutritional values and freshness of milled-on-demand flour.

A More Practical Approach (Maybe)

Many of you may immediately view this little adventure as very impractical - with good justification, too. However, it at least is an example of creating flour of various grades at home, a drastically scaled down version of what happens in a real mill, doable at home, even if a little too large for the majority of home bakers.

I believe a simple version of this could use one #60 sieve and one #40 sieve and a Retsel Stone Mill or other similar mill that provides good control of the coarseness of the flour output. If set to much coarser settings, multiple passes could be performed on the coarse results caught in the #40 and #60 sieves. The sifting could be done by hand, even in quantities up to around 2Kg, although it is a little tedious and laborious. Maybe only 3-4 passes would be done, to minimize the labor, but the results of running tempered berries through at a coarser setting, and then re-milling more finely the coarse results caught in the sieve and re-sifting should allow the extraction of a reasonable flour similar to Golden Buffalo, just as shown above.

Where From Here

Even with a sieve shaker, the sifting is the most tedious and time consuming part of this process. The milling for all the steps combined for about 2Kg of berries was probably only about 10-15 minutes. The milling goes very quickly. However, the sifting drags on for 20 minutes at a time at first. Later steps are quite fast, and the last couple of passes can be done more quickly by hand, given the reduced amount of product.

I've ordered a Meadows Mill Eccentric Sifter (Goetter, hehe?) to add to the burgeoning list of equipment in the workshop. My hope is that this will make the sifting take only minutes at a time, more comparable and well matched to the milling speeds. Of course, this is all massive overkill for home baking. Yes, massive, massive overkill, no question. However, it is a hobby pursued with passion that may not always make sense in practical terms. It is the beauty of the home engineering, the resourcefulness required, and the delicious freshness of the bread that all contribute to the enjoyment.

Another remaining nagging missing piece of the puzzle is a flour analysis tool that would allow more thorough understanding of all the outputs, such as protein content, moisture content, water absorption, and ash content. Maybe I've figured out the ash content using the conductivity method described previously, but it seems to take a good 12-24 hours to get useful results from it. I'd like to be able to get quick turn-around for these measurements, in order to optimize the milling and sifting strategies.

Update (1/28/07)

I received the Meadows Eccentric Sifter (see video) and conducted a milling, sifting, and baking session (see photos), as well as some home ash content tests to check out the results with the new sifter. The Meadows sifter is far faster than my original approach with a sieve shaker and produces 4 separations simultaneously with great ease.

The sieve shaker had some advantages, in retrospect. You could inspect the results easily and fine-tune the sifting strategy very easily and quickly. Also, very little product is lost using the mining sieves, which is valuable for the smaller amounts I tend to do each time. The Meadows Sifter kept a couple of pounds in it, probably in the nooks and crannies of the wooden sieves and some built up on the fabric sleeves used to transport the flour. The Meadows Sifter made it more difficult to inspect or change the sifting process, as the sieves are tightly bolted down with wing nuts on long threaded rods. You can open it up, but it's much more time consuming than it is to detach and separate the mining sieves.

In this milling session, I tempered the wheat to a 13% moisture content. The tempering process was shortened to only 12 hours as a result of impatience to test out the sifter. The first pass through the Meadows 8 Inch Mill was troublesome. The breaker tripped even though I had the mill set to a fairly wide opening of about 1/8 turn on the adjustment screw. After several tries, I was able to complete the first pass with the screw open between 1/4 and 1/8 turn. A while later, I tried running untempered wheat at 10.6% moisture content through the mill, and it also had a tendency to jam the mill. Since I really don't have the slightest idea what the right opening is for the first pass through the mill, I'm not sure what to conclude. On the one hand, the milling went very smoothly with wheat tempered to 14% moisture content for more than 24 hours. On the other hand, the Meadows representative seemed very clear that 13% moisture content or less was preferred for the Meadows Mill. However, when I used less moisture and less tempering, the milling seemed more difficult on the first pass. All subsequent passes were uneventful, even on the finest settings.

After completing the milling session, I ran some home ash content tests. Clearly the yield of lower ash content white flours was much lower. I believe this again had to do with using lower moisture content wheat tempered for a shorter time. The flours seemed more like my earlier attempts with the Retsel mill, where one or two passes with untempered wheat berries resulted in a flour much closer to a whole wheat flour.

The sense that the flours were darker was corroborated by the home ash content tests, which showed the flour coming the the #60 sieve had an ash content almost as high as Heartland Mills WW flour (I'm making my flour with Heartland Mills "Milling Wheat (M2)". Output from subsequent passes had an ash content close to 1%, whereas in my earlier attempt with 14% moisture content 24 hour tempered berries, the flour from passes 3-4 that was the whitest had an ash content of about .75%. I think this explains why my earlier one or two pass attempts made loaves that seemed so much more like whole wheat loaves than my more recent multi-pass attempts with well tempered 14% moisture content wheat.

In order to get a flour something like Heartland Mills Golden Buffalo, I had to accept a lower yield this time. The home ash content tests take at least 24 hours of soaking, so I used color and inspection of the flour, plus the knowledge that the middle passes would be lower in ash content to blend the outputs to get a flour of the same approximate "color" as the Golden Buffalo. My "high touch" method came out to have an ash content almost equal to that of Golden Buffalo, but my yield was only about 65% this time, whereas I had a lower ash content with close to 80% yield in my earlier attempt with berries at 14% moisture content and tempered for more than 24 hours.

The loaves were made without any diastatic barley powder this time, and the crumb had no hint of gumminess. The color of the crust stayed slightly lighter than before. The gluten seemed a little better this time, which makes me wonder if the protein content or quality from this session was slightly better. It's hard to say, because I reduced the hydration based on the previous results, and this dough may have behaved well just because of more optimal hydration. However, maybe the gluten quality is somehow improved due to the different ash content, tempering method, and sifting method.

The loaves that resulted were very good. As noted above, the crumb was a touch darker than the last one, which correlates with the higher ash content measurement. However, the crumb was still much closer to a white bread, similar to the last one, as opposed to earlier attempts that were clearly closer to a whole wheat bread.

Sourdough Pagnotta (1)

Sourdough Pagnotta (1) Sourdough Pagnotta (2)

Sourdough Pagnotta (2) Sourdough Pagnotta (3)

Sourdough Pagnotta (3) Marcel's Grandmother's Potato Bread (1)

Marcel's Grandmother's Potato Bread (1) Marcel's Grandmother's Potato Bread (2)

Marcel's Grandmother's Potato Bread (2)